The Agony and Reward of Automaticity

The process of our teaching has uncovered a few challenging tasks. Such tasks usually involve enduring some unavoidable pain and suffering on the way to a valuable goal. When people know why they need to go through the suffering, it becomes more bearable, and this knowledge motivates people to push through until the task is completed.

To me, it seems that one of our particular tasks is to produce automaticity in our kids’ arithmetic skills. Automaticity is the ability to do big things without having to constantly think about the little details. An example of automaticity is the use of a skateboard for commuting. Confident skateboard commuters are able to focus on such high-level tasks as wayfinding, navigating sidewalk and/or street congestion, noticing and adjusting to commute conditions, and optimizing commuting routes to save the greatest possible time or effort, without having to worry about the low-level tasks of figuring out how to balance on a skateboard, how to start and stop safely, and how to keep from eating it once they are in motion. Automaticity can only be produced by practicing and/or memorizing the little details until a person knows them by heart. A novice skateboarder who has not mastered the little details spends so much time trying to figure them out that he or she has very little processing power left for higher order tasks such as figuring out the best route to his or her destination.

Automaticity is the key to mastering arithmetic, just as arithmetic is the key to mastering algebra and calculus. Without it, kids will not be able to handle college mathematics courses. However, automaticity has been de-emphasized in many American public schools. This is especially true of schools whose student population consists of a large percentage of children of color. The result is that it is impossible for these kids to quickly use the standard arithmetic algorithms to solve problems with multiple-digit numbers. This leads to an inability to solve problems involving ratios, averages, or formulas, and thus leads to a handicap when these kids try to tackle algebra. This is why, over the last several years, there has been an explosion of kids who have found out that they need remedial math courses when they try to go to college after high school. One case is particularly troubling – namely and African-American girl who worked hard in high school, who did all her homework, and who was enrolled in honors classes. She graduated with a GPA of 4.2 out of 5. But when she tried to enroll in college, she failed the math placement test and was told that she had to take remedial math classes.

This is happening a lot. And it is happening especially to students of color. The result is that many students of color drop out of college. The reason why many of these students wind up needing remedial math education is that their elementary school teachers never worked with them to achieve automaticity. Personally, I think a lot of this is deliberate, because it is a convenient way to maintain a permanent underclass of people whose education has made them fit only for menial labor. If these people also belong to communities which have historically been marginalized and oppressed, so much the better, as far as the masters of the dominant culture are concerned. But this state of affairs is something which the oppressed should refuse to accept.

So if the school systems which supposedly teach our kids deliberately fail to produce this kind of skill, it’s up to us to produce this skill. And because automaticity of large-scale math operations depends on memorizing single-digit math facts, we have been asking parents to set aside 20 to 30 minutes every night to work on memorizing single-digit math facts. This can be somewhat dry work (although there are games and rewards that can spice it up a bit). Yet as students continue in this work, they discover that they have increased their power to understand the world, and in understanding their reality more fully, they can begin to transform it.

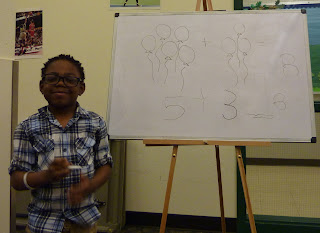

And it's possible to start this work even with very young children, which, by the way, is what was done with the children of my generation. It should not seem a strange thing to be able to teach four and five year old children how to count, how to recognize numerals and number names, how to write numerals, and how to add and subtract. The kid shown in this week's post has had two learning sessions with us, and he's loving it. For our part, we are happy to share in his joy. Watch him practice writing numerals:

Comments